The most popular animated film in 2025: Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King

Under the general downward trend of the current Chinese film market, “Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King” (hereinafter referred to as “Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King”) is a highly controversial work. In addition to the box office crown of “ No. 1 in Chinese Film History “ and a wide range of social topics, it not only continues the IP popularity and cultural symbol value accumulated by its predecessor “Nezha: The Devil Boy Comes into the World”, but also makes bolder explorations in terms of technology, narrative and aesthetics. However, the price of this exploration is that the film presents a clear sense of separation - both the precise catering to market demand and the loss of control of creative ambitions; both the breakthrough of visual wonders and the tendency to compromise in terms of style coordination and narrative depth

The Dilemma of Creation: Imbalance between Narrative, Technology and Aesthetics

1. Scattered and fragmented narrative: lack of focus under the grand proposition

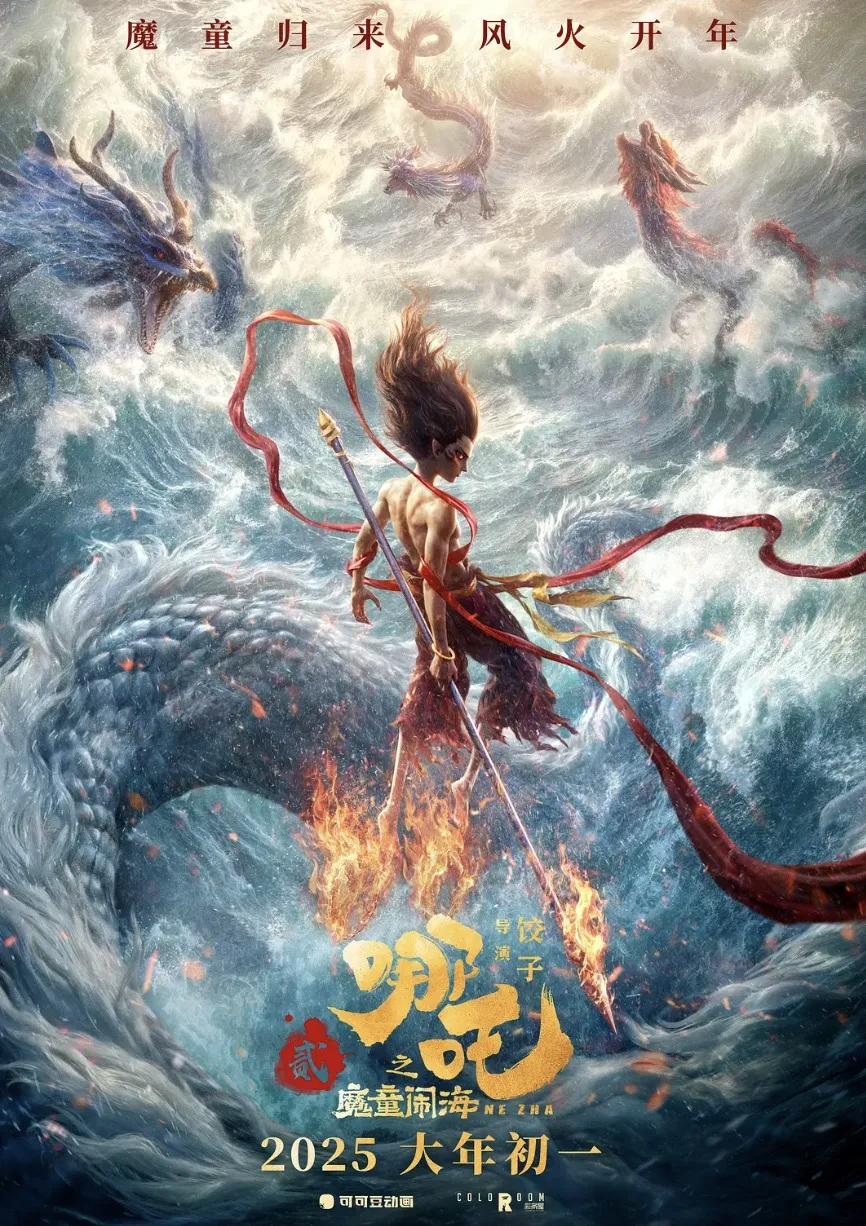

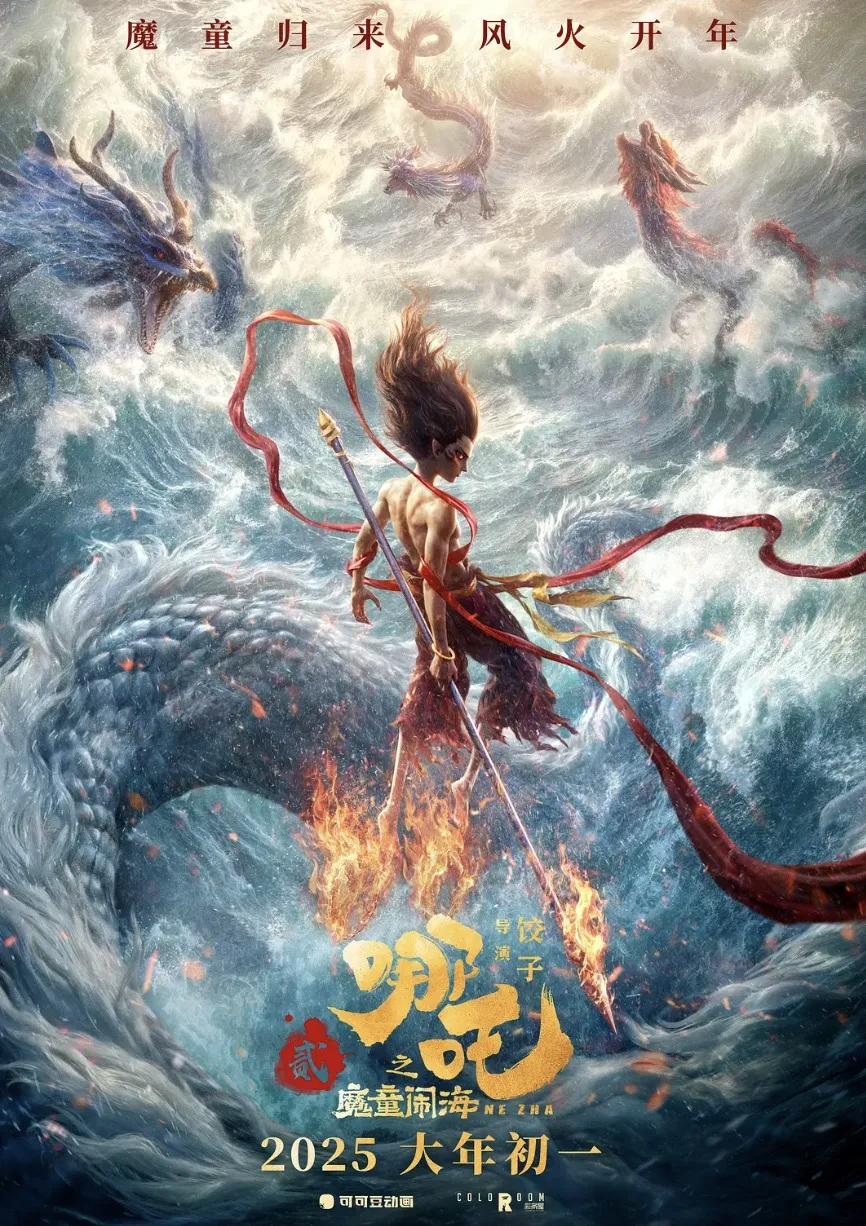

Poster of Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King

“Nezha Conquers the Dragon King” has many tool characters, abrupt plot twists, a lack of IP core, and written lines at the text level. The film attempts to carry multiple propositions in a single text: from class oppression, power criticism to individual awakening, and even mixed with metaphors of international politics. However, this “greed for more and more” leads to a blurry narrative main line. The first half of the film uses the absurd setting of “cultivating immortals and taking exams” to satirize structural oppression, but the second half turns to the tragic epic of the defense of Chentangguan. There is a lack of natural transition between the two, and the plot advancement relies too much on external events (such as the death of Mrs. Yin) rather than the internal growth logic of the characters. For example, Nezha’s transformation from a naughty boy to a hero should have been gradually completed through ethical choices, but the film used the mother’s sacrifice as a catalyst, weakening the persuasiveness of the character’s arc. This sense of rupture exposes the creators’ swing between “epic sense” and “commerciality”: they want to continue the theme of “changing fate against the sky” of the previous work, and want to deepen the connotation through social metaphors, but eventually fall into the dilemma of piling up themes.

What is even more alarming is that the film’s deconstruction of traditional myths is superficial. For example, the setting of Shen Gongbao as a “small town test-taker” reflects the class anxiety of contemporary youth, but his motivation for behavior (such as the massacre at Chentangguan to keep a secret) is still simplified to “inevitable evil” and lacks deeper psychological portrayal. This symbolic treatment makes the character a mouthpiece for the topic rather than a flesh-and-blood individual.

Stills from Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King

2. Mixture of Artistic Styles: The Lost Aesthetics of the East

In its visual presentation, “Ne Zha” attempts to blend Eastern and Western aesthetics, but the result is a confusion of styles. In terms of scene design, the minimalist temple of Yuxu Palace and the ruins of the Dragon Palace in the East China Sea form a sharp contrast, which could have been a visual metaphor for power and oppression. However, the former’s imitation of the multi-dimensional space of “Interstellar” and the latter’s reference to the gloomy cabin of “Pirates of the Caribbean” weakened the unique charm of Eastern mythology. In addition, in terms of modeling design, the style jump between realism and “comic sense”, the infiltration of Japanese two-dimensional elements, and the mixture of Westernized cartoon design in “Ne Zha” have not been solved in the sequel. The character modeling has an obvious tendency to “become an Internet celebrity”: Nezha’s smoky makeup and Ao Bing’s Korean handsome face cater to the aesthetics of young audiences, but they run counter to the divine temperament of traditional mythological characters. This “international” transformation is essentially a compromise with market trends, rather than an expression of cultural confidence.

Stills from Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King

3. Roughness of 3D technology: limitations of industrial standards

Although the film boasts of “special effects upgrade”, the three-dimensional production of some scenes is still rough. For example, the physical dynamics of the chains when the beasts leave the palace lack details, the hair and scales of the beasts are stiff, and the group movements in the long-range shots are even more rigid, like game NPCs. This technical defect is particularly glaring on the IMAX screen, exposing the shortcomings of the Chinese animation industry in detail polishing. In contrast, similar Hollywood works (such as “Spider-Man: Across the Universe”) have achieved a stylistic breakthrough through the fusion of hand-painted and CG, while “Ne Zha” is still at the stage of “stacking special effects” and lacks innovation in artistic language. The so-called “large quantity and full” special effects superposition is more about the audio-visual pleasure and instant shock at the spectacle level, but it is slightly empty and weak in terms of concept and aesthetics.

Special effects in Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King

3D Production in Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King

4. Out - of -control sound design: conflict between dialect and emotion

The film’s sound processing has obvious flaws. The volume of the soundtrack in the battle scene suddenly increased, covering up the character’s lines and making the meaning unclear ; the film’s lines are designed to integrate multiple dialects, such as Shaanxi, Tianjin, Sichuan, etc., which is indeed considered to serve the character’s personality, and can also be regarded as a rebellion against orthodox “Mandarin”. However, the mixture of dialect systems makes the listening experience confusing to a certain extent. The “decorative” nature of dialects as an auditory level is over-amplified, and the expressive function of the lines is weakened, and even to a certain extent interferes with the narrative rhythm . What’s more serious is that the emotional expression of the voice actors is sometimes out of touch with the character’s state: Nezha’s roar when he lost his mother lacks layers, and Shen Gongbao’s tragic monologue weakens the appeal due to unclear pronunciation. As the soul of animation, sound should enhance the sense of immersion, but “Ne Zha Conquers the Dragon King” repeatedly loses points in this aspect.

Taiyi Zhenren speaking in dialect in “Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King”

Dubbing scene of “Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King”

5. Excessive game scenario: the contradiction between interactivity and narrative

The “strong invasion” of game aesthetics in animation art may lead to the marginalization of animation audio-visual and sensory narratives , and weaken the diversity of animated films in the artistic language paradigm . In “Ne Zha Hai”, the interactive strategy of game narrative is particularly vivid: the “upgrade and fight monsters” mode of Xiu Xian Kao Biao , the “tower defense” combat design of the Chentangguan defense battle, and even the boss-like image of Wuliang Xian Weng, all reflect the imitation of game narrative. Although this design fits the “high-paced” viewing habits of the short video era, it also leads to the sacrifice of narrative depth. For example, the section where Tianyuan Ding suppresses the Dragon Palace could have been rendered tragic through slow motion, but it was processed into a show-off “skill release animation”, and the emotional tension was gone. When a movie becomes a vassal of “playability” , it is very likely to over-pursue the visual impact of gamification, while ignoring the tendency of narrative emotional depth and character creation. When the character loses its complete arc and self-consistent motivation, the contradictory relationship is externalized into a stack of battle spectacles of “fighting for fighting”, and its uniqueness as an artistic carrier is in jeopardy.

Scenes from Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King

The way out: innovative attempts under business logic

1. “ Fast - forward” action design: the victory of short video aesthetics

Despite the flaws in the narrative, the action design of “Ne Zha Dou Hai” is revolutionary. The film abandons the “introduction, development, turn and conclusion” style of traditional animation and instead adopts a combination of “fragmented editing + high-speed camera movement”. For example, the soul battle between Nezha and Ao Bing and the multi-tentacle attack of the sea monster octopus, the number of special effects shots alone is as high as 1,948, surpassing the total number of shots of “Ne Zha” of 1,864 . This “information overload” strategy accurately captures the attention law of Generation Z - in the media environment dominated by Douyin and Kuaishou, the audience has become accustomed to the stimulation mode of “instant feedback”. “Ne Zha Dou Hai” successfully transformed the movie into a “visual marathon” through the “gamification” of action design. Its market response proves that this experiment is radical but effective.

Shot design in Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King

2. Continuation of IP shaping : consumption of rebellious symbols

he success of the previous work “My destiny is in my own hands, not in the hands of God” is essentially to shape Nezha into a cultural symbol of “rebel”. Although the sequel did not produce the same level of golden sentences, it further strengthened the universality of this symbol through settings such as “flesh symbiosis” and “reconstruction of rules”. When Nezha roared “If the world does not tolerate it, I will turn the world around”, the object of his resistance has been sublimated from fate to structural hegemony. This transformation not only echoes the collective anxiety of contemporary youth about “involution” and “996”, but also injects lasting vitality into the IP. It is worth noting that the film’s presentation of “rebellion” is always within a safe range: Nezha eventually returns to the mainstream order as a savior. This “limited rebellion” just conforms to the survival law of commercial blockbusters.

3. Industrial breakthrough of large scenes: the ambition to match the real-life blockbuster

On the technical level, the grand scenes of “Ne Zha” have indeed reached a new height for domestic animation. In the battle to defend Chentangguan, the long shot of the monsters pouring down from the void rift like a waterfall is comparable in scale and complexity to the Battle of Helm’s Deep in “The Lord of the Rings”; the section where the Tianyuan Ding descends in Yuxu Palace creates a sense of science fiction epic like “Dune” through the aesthetics of giants (BDO). These scenes prove that “ big scenes “ and “big effects” can focus on presenting the grand atmosphere and ingenuity of details in the construction of the “other world” scenes of animation, and with the audio-visual language and scene scheduling, it gives people a sensory shock. The Chinese animation industry has the ability to control high-difficulty visual effects, and its technical indicators such as rendering accuracy and physical simulation are even not inferior to some real-life blockbusters. Although there are still flaws in the details, this strategy of “fighting big with big” has undoubtedly opened up new possibilities for domestic animation.

Concept design in Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King

The marketing of “Ne Zha Hai” can be called a “textbook-level” case. First of all, from the perspective of marketing budget allocation, new media channels account for 62%, and traditional channels are compressed to 18%. The movie trailer was pre-laid on social platforms such as Douyin, Weibo, and Bilibili. After the release, the film was further promoted on the Internet platform through the tap water dissemination of short video platforms in the form of sharing behind-the-scenes footage, sharing viewing experience, imitation makeup challenges, and dubbing challenges. In terms of content marketing, on the one hand , the film created social discussions through topics such as “cultivation exams” and “green card metaphors”, transforming the viewing behavior into a cultural event; on the other hand, the main creators actively linked up with the academic circle, such as juxtaposing the oppression of the dragon clan with the “Bretton Woods system”, and even appearing on the cover of international academic journals, to enhance the style of the work with the attitude of “cultural output”. In addition, the combination of “high-energy mixed editing + emotional interpretation” of the short video platform effectively covers audiences from different circles. This dual-track strategy of “pan-entertainment + academic endorsement” not only amplifies the value of IP, but also reshapes the publicity and distribution paradigm of animated films.

While clarifying the positive role of the publicity and promotion link in the national awareness and discussion of the film, we should also be more rational and prudent in recognizing the potential hidden dangers of excessive marketing for the industry ecology. First, it is the squeeze on the publicity and broadcasting space of small and medium-cost films. Excessive marketing leads to the concentration of resources in a few blockbusters. Even if the small and medium-cost films are of high quality, they may not be able to attract the attention of the audience due to insufficient scheduling; secondly, it is the destruction of the healthy ecology of the film market. Long-term over-reliance on marketing will cause the film market ‘s evaluation mechanism for “good films” to further exceed data and traffic, deviate from the film’s own expression of concepts and aesthetics, and may cause the film market to fall into a vicious cycle of “bad money driving out good money”, weakening the industry’s innovation momentum; finally, it is still necessary to realize that in the dimension of viewing experience, excessive marketing of a certain film will narrow the audience’s range of choices and affect the diversity of viewing experience.

Marketing of “Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King” at Weibo Night

Director Jiaozi of “Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King” is promoting the film

The most commendable thing about the film is its metaphorical courage for social reality. From the satire of immigrant anxiety in “Yuxu Palace Green Card” to the criticism of the fanaticism of converts in “Lu Tong He Tong”, and even the bold insinuation of “New Coronavirus = Biological Weapons”, the creators used mythology as a shell to complete a panoramic deconstruction of contemporary society. Although this strategy of “borrowing from the past to satirize the present” is straightforward, it gives animation a rare realistic weight. What’s even more rare is that the film did not stay at the critical level, but through the “physical symbiosis” of Nezha and Ao Bing, it proposed the philosophical proposition of “coexistence of good and evil”-this exploration of complex human nature is particularly precious in commercial animation.

Stills from Nezha: The Devil Boy Conquers the Dragon King

Conclusion: Standing at the crossroads of Chinese animation

The success or failure of “Ne Zha” reflects the deep contradictions of Chinese animation: on the one hand, the progress of industrial technology and the expansion of market scale have provided creators with unprecedented freedom; on the other hand, the excessive reliance of capital on IP and the pursuit of short-term profits have continuously squeezed the space for artistic expression. The “sense of tearing” in the film is the concrete presentation of this contradiction.

As scholars, we have always believed that animation is not only an entertainment product, but also a carrier of cultural spirit. If Ne Zha Xiao Hai can balance the gap between commerce and art with a more distinct theme, a more self-consistent narrative, a purer aesthetic, and a deeper humanistic care, it may really be able to open up a “new myth universe” as the creators wish. On the contrary, if we continue to indulge in “special effects involution” and “topic piling”, the so-called “rise of Chinese animation” will eventually become a footnote to the capital game.

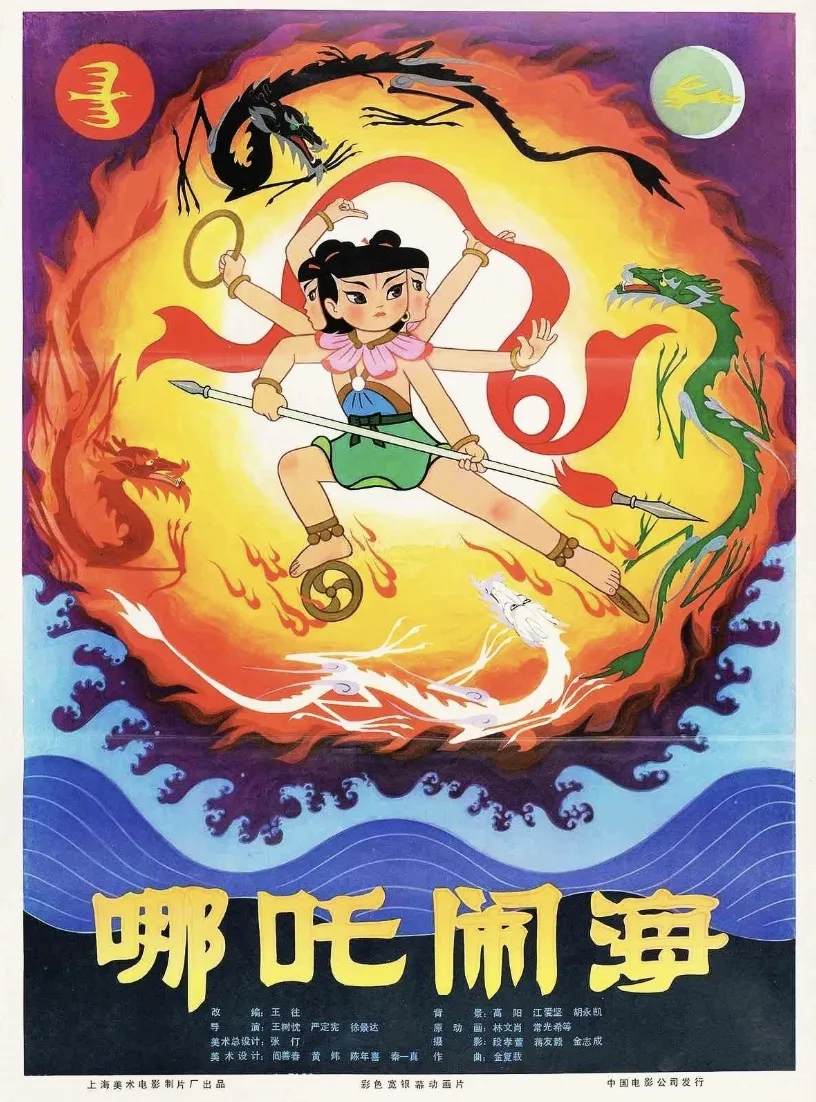

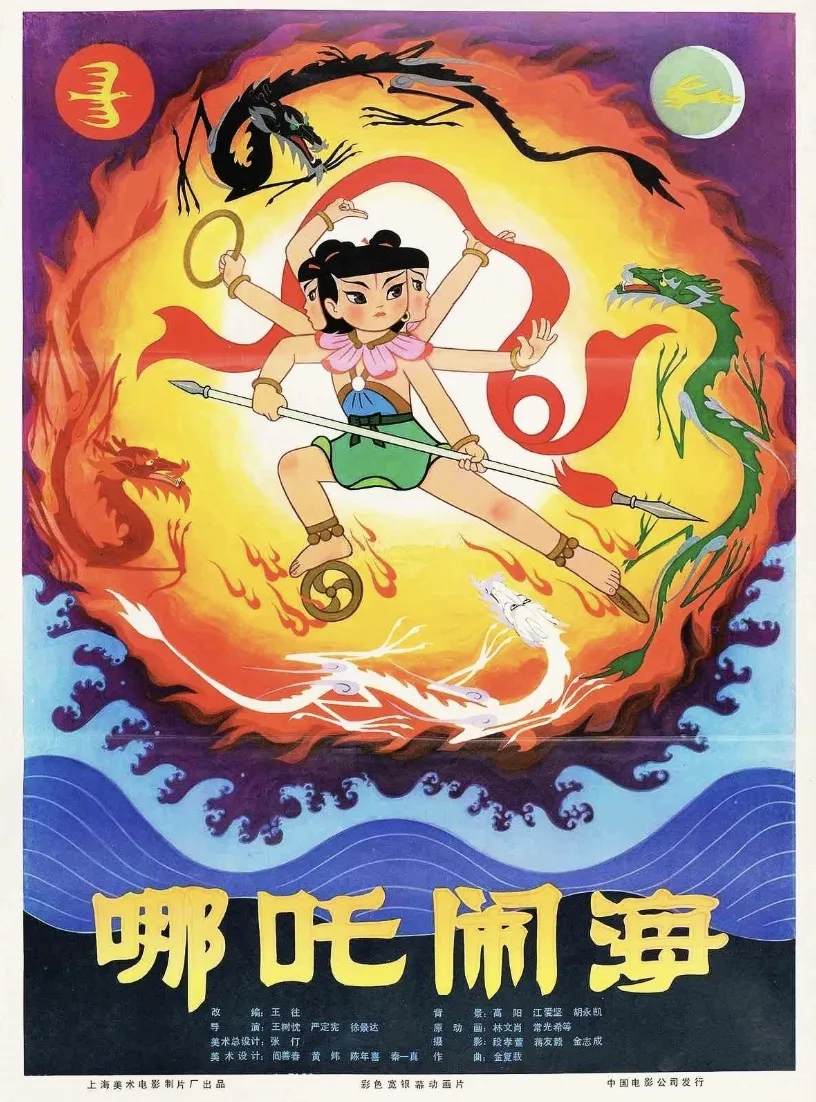

Nezha Conquers the Dragon King, produced by Shanghai Animation Film Studio in 1979

Written by: Chuan Ye, Professor of Drama and Film

Layout: Wang Fang, Li Na, Zhang Xiaoyan

Editor: Xiao Yan, Li Fei

Advisor: Fan Beilu