“Oppenheimer” Director: Christopher Nolan

This article is a detailed introduction to the core strategy of shooting this film by director Christopher Nolan, ASC member Hoyte van Hoytema, and the main creatives of the film’s production team.

Author: Ian Marks

In the movie “Oppenheimer”, there is a scene in which U.S. Army General Leslie Groves (played by Matt Demon) tells the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (Gee) Cillian Murphy (Cillian Murphy)] Germany has launched a nuclear weapons program.

It was 1942, at the height of World War II, and the U.S. government wanted to have its own atomic bomb. The core issue at that time was not whether this weapon could be developed, but which country could take the lead in developing it.

In Oppenheimer’s mind, it was all about the movement of particles, the pulsation of energy, and perhaps the end of the world. He seriously accepted the task of building an atomic bomb, believing that if this powerful new technology was developed by a righteous party, It can benefit mankind. Therefore, “Oppenheimer” may be seen as a story about how people make themselves realize their dreams. The same goes for the filming process of the film.

Think boldly

Director Christopher Nolan and cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema (ASC, FSF, NSC) take the lead in this biopic, shot entirely in large-format color and black-and-white film, entirely through the camera. Capture hundreds of unique visual effects shots that forgo traditional lighting methods.

“It’s important to emphasize the purpose behind all these technologies,” Van Hoytema said. “Every advancement in filmmaking, whether it’s sound, special effects, or technology like forward flash, is because someone invented it to satisfy the needs of the film’s creation. needs. This is very important when I start shooting a new project, because every film has its own unique language and comes with specific challenges.”

“Oppenheimer” is Van Hoytema’s fourth film with Nolan, who previously collaborated on “Interstellar,” “Dunkirk” and “Tenet.”

All the while, the cinematographer continues to innovate his shooting techniques, including using daytime and nighttime technology (combining ArriRental Alexa 65 infrared cameras and Panavision System 65) in Jordan Peele’s 2022 film No mm film camera), as well as the special snorkel aerial lens used to shoot the aircraft cockpit in “Dunkirk”. These technological innovations are inseparable from Dan Sasaki, senior vice president of optical engineering and lens strategy at Panavision and a member of the ASC Association. )’s blessing.

“I thought a cinematographer’s job was about more than just photography, so I brought in special effects people, engineers, and manufacturers to work on some amazing tools to achieve the images I had in my head but didn’t know how to capture.”

Van Hoytema even designed the production tools himself, starting with small CNC machines and lathes, and later built a complete metalworking shop in the garage of his Los Angeles home to create precision custom parts. “Everything I’ve made over the years can be found on our set, and it’s been put into camera dolly, lighting trucks and mechanical cars,” he said.

Experience-focused movies

Nolan and Van Hoytema’s creative philosophy has always emphasized evoking the audience’s touch through movies. “Whether it’s something huge or tiny, we want the audience to experience it first, rather than make an intellectual judgment about it,” the cinematographer said.

From a technical point of view, this idea can be realized through practical means, such as using large format film. During the filming of “Oppenheimer”, multiple 5-hole Panaflex System65 Studio cameras and 15-hole Imax MSM9802 cameras and MKIV cameras were used, with Panavision Panaspeed, System65 and Sphero65 lenses, as well as a customized 40mm close-range fixed focus lens.

Murphy (right), accompanied by stunt coordinator Dan Brown, inspects an Imax camera kit prepared for filming at the Trinity Nuclear Test Site

Van Hoytema believes that, conceptually, it is a question of restraint. “Otherwise, the final effect could be overwhelming.” The filmmakers eschewed a composition in which the horizon occupied the bottom third of the frame, which is standard practice for Imax films. “We could frame the shot at the top of the frame with lots of white space for dramatic effect, but in a 70mm Imax film, we put the horizon line directly in the center of the frame, respecting the way the viewer’s eyes naturally scan and maximizing the use of peripheral vision. Effect.”

The cinematographer explains: “It’s a more functional image. The basic information is conveyed directly to the viewer from the center of the frame, and peripheral vision brings the image to life and adds a sense of atmosphere – it’s not that the image transcends the frame and its meaning. Rather than communicating through consciousness, we try to interact with the audience in a more direct and intuitive way.”

the best and the brightest

Oppenheimer did not invent the atomic bomb alone. His R&D team assembled some of the best minds in science at the time, including physicists Edward Teller, Isidore Isaac Rabbi and Enrico Fermi [led by Benny Safdie and Dr. Played by David Krumholtz and Danny Deferrari]. Even Albert Einstein [played by Tom Conti] contributed.

“Oppenheimer” stills: The day before the nuclear explosion test, the “Trinity” nuclear test site encountered a violent storm

Van Hoytema also worked with a group of professional partners when shooting the film, including first photography assistant Keith Davis, lighting engineer Adam Chambers, lighting system designer Noah Noah Sha-in, machinist Kyle Carden, DNEG visual effects supervisor Andrew Jackson, special effects supervisor Scott Fisher, and Panavision optical expert Sasaki.

unusual request

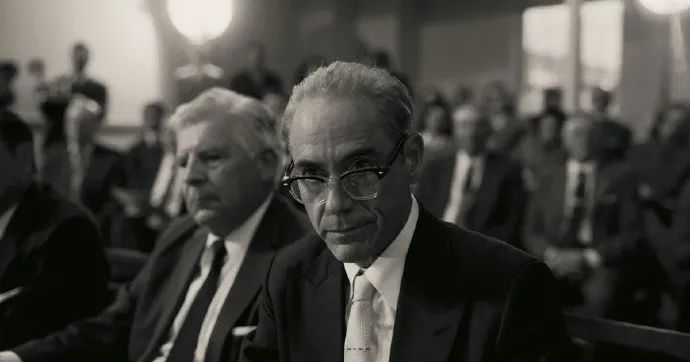

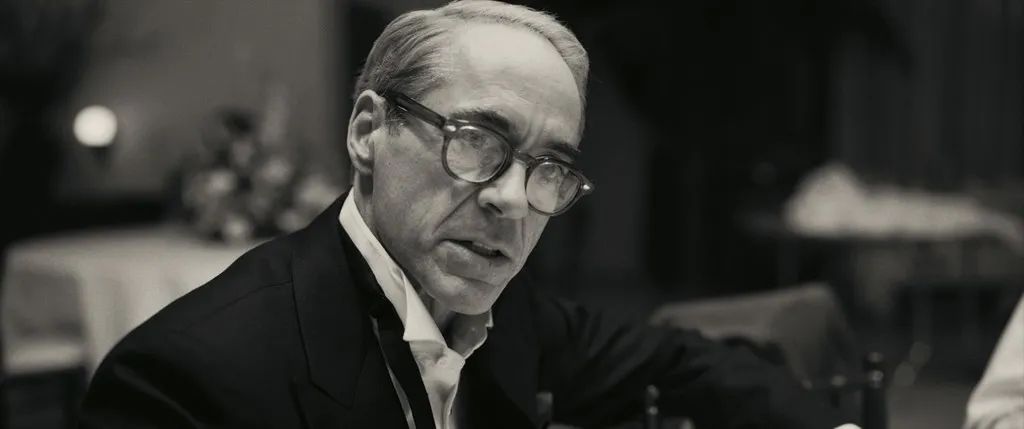

They also teamed up with Kodak and FotoKem to create the unprecedented 65mm EastmanDouble-X5222 black and white film. “Chris wanted to visually distinguish the Oppenheimer and Lewis Strauss stories, and all of Strauss’s perspectives were shot in black and white,” Van Hoytema explains.

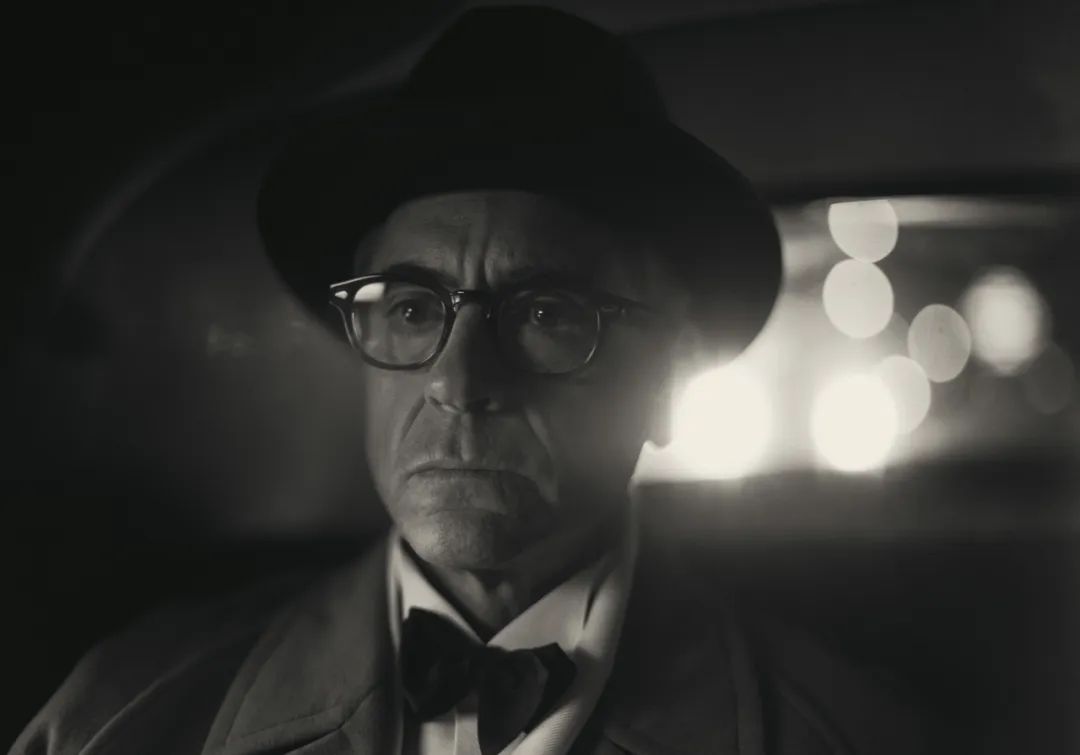

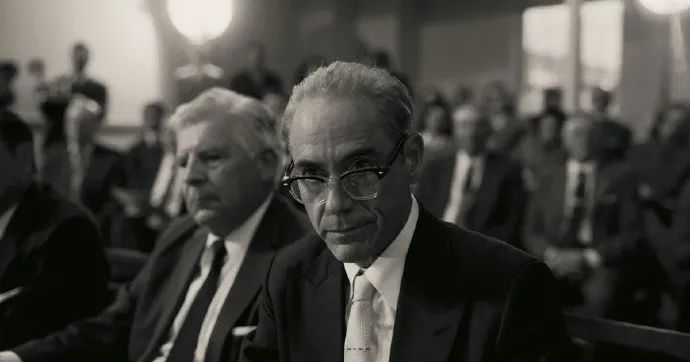

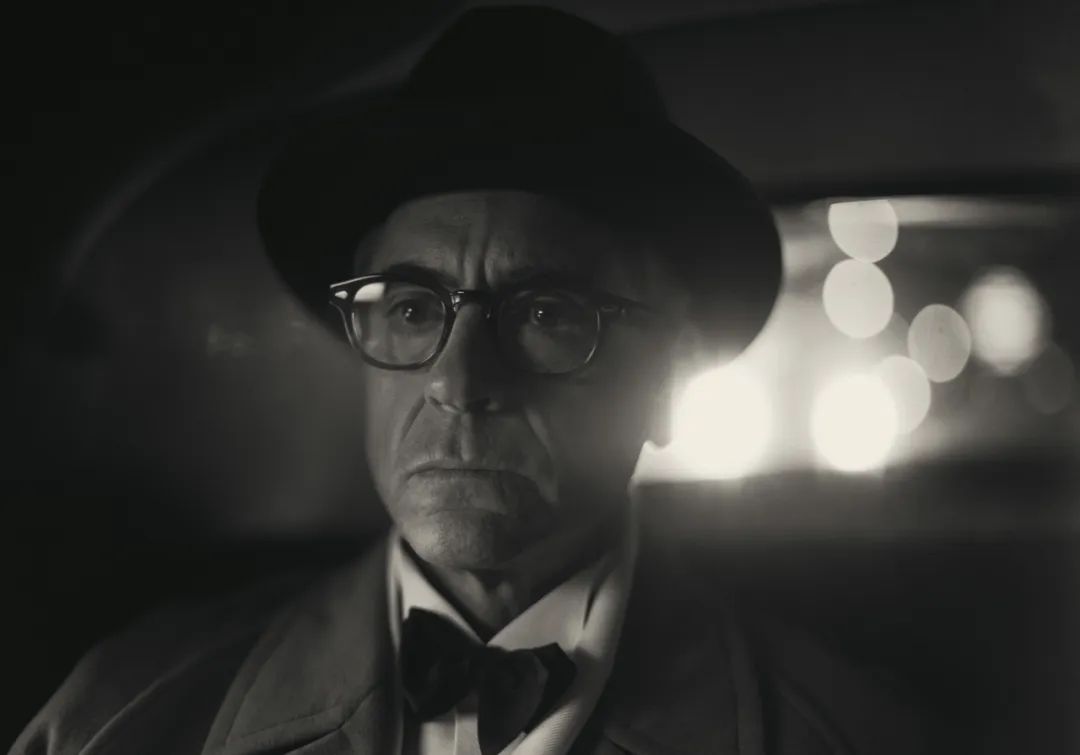

Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) was appointed chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission by President Harry S. Truman (Gary Oldman), who later believed that Oppenheimer was responsible for national security. threatening.

Cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema holds the camera close up to capture Robert Downey Jr., who plays the chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission in the film

The film’s filmmakers initially encountered technical problems when they requested this from Kodak, primarily because Double-X film had never before been produced in 65mm (which required cutting and perforation). This means that Kodak needs to improve the film production and strictly control the quality to ensure that there will be no film problems during the filming process.

Strauss pondered his future and that of Oppenheimer.

“It was because of our persistence,” says Van Hoytema, “that Kodak agreed to try it.” Black-and-white film (as opposed to the carbon black antihalation layer of color negative film) has a thinner antistatic layer and is susceptible to the typical chrome plating of film cameras. Effect of exposure artifacts on the platen. To solve this problem, they made a special “black oxide” vacuum platen for Imax film cameras.

At FotoKem, color processing equipment for 65mm film typically requires up to three days in the darkroom for cleaning and chemical development. “It was very nerve-wracking at times,” Van Hoytema recalls. “We had to plan our shoots around black-and-white scenes that sometimes wouldn’t be developed until the next week, so we would also shoot those scenes in color. version as a backup. It’s all the same content, just shot again and again on different film stock.”

Soft light and hard light

Usually, when shooting color scenes, the cinematographers of this film will use Kodak Vision3500T5219, 50D5203 and 250D5207 films, and use lighting equipment such as ArriSkyPanel, Orbiter, Astera and HMI as well as UltraBounce reflectors to create large soft light, while using black and white film The lighting was more intense when filming, such as the Senate hearings for Strauss to join the cabinet.

For the latter, Chambers utilized a number of period-correct “basher” tungsten lights—500- and 1,000-watt bulbs, for local and general lighting—that were mounted on light stands, just like those used on television sets of the time. use. The intensity of the lights was controlled directly from the crew’s dimmers, “They were harsh, but they looked great,” Chambers said.

“Beehive Lamp” by van Hoytema

Another widely used lighting tool is Van Hoytema’s own “honeycomb lamp” using COB light source, which uses a printed circuit board to integrate a daylight-balanced LED lamp head, radiator and ballast. The entire lighting assembly measures 18 inches and the perimeter of the honeycomb light is 10 inches.

Nolan, Van Hoytema and crew filming Murphy in the office

Modular design of lights means that individual lamps can be combined to create a stronger light source, or the COB light source can be removed from the ballast for special purposes. “They’re very versatile,” says Chambers. “We’ll make them waterproof for use in rain or underwater scenes, or they’ll be modified for use in a variety of difficult shooting conditions, primarily for special effects and Automotive scenes because they can generate a lot of heat to provide adequate lighting. Equipped with a focus lens, they are as powerful as an M18 light.”

Various special effects

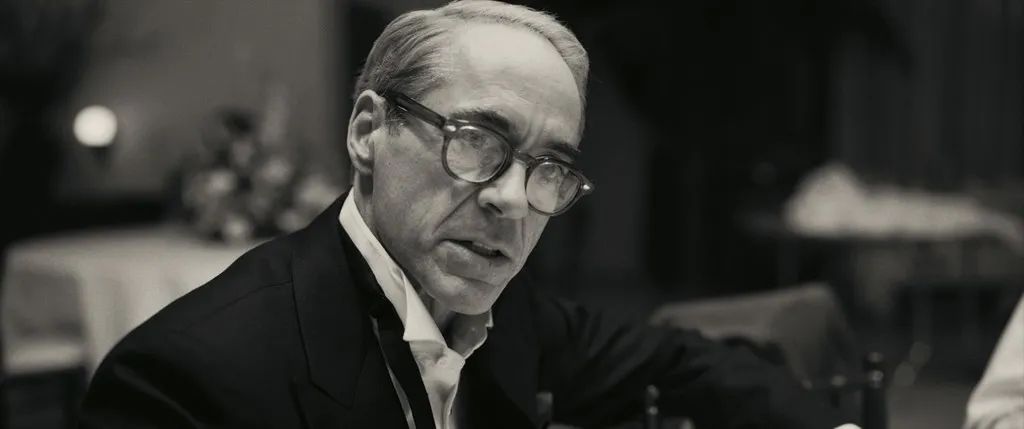

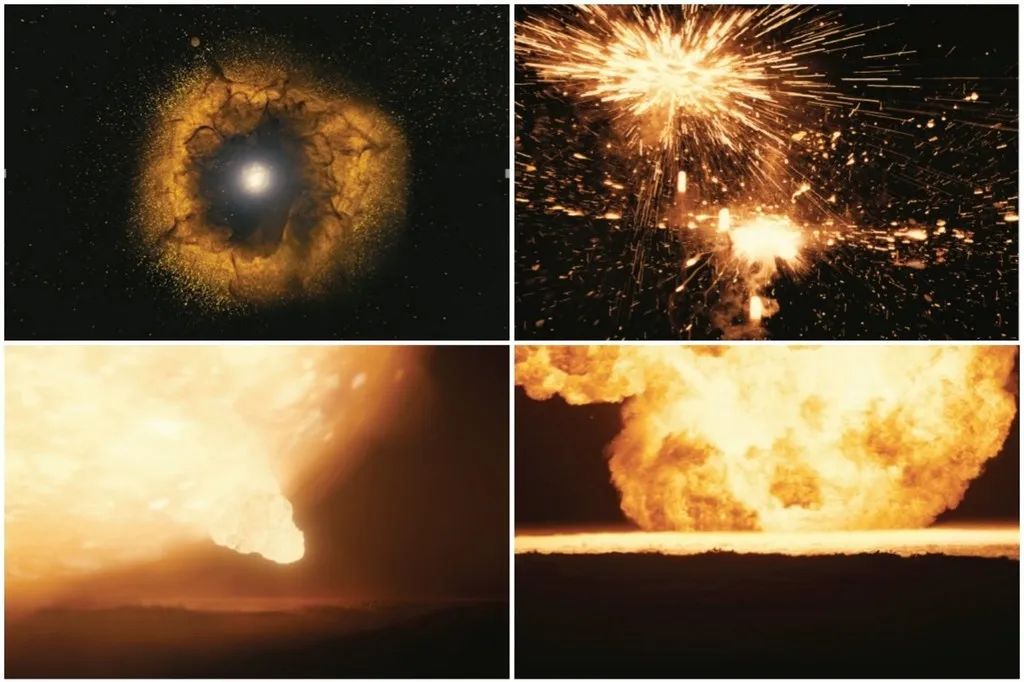

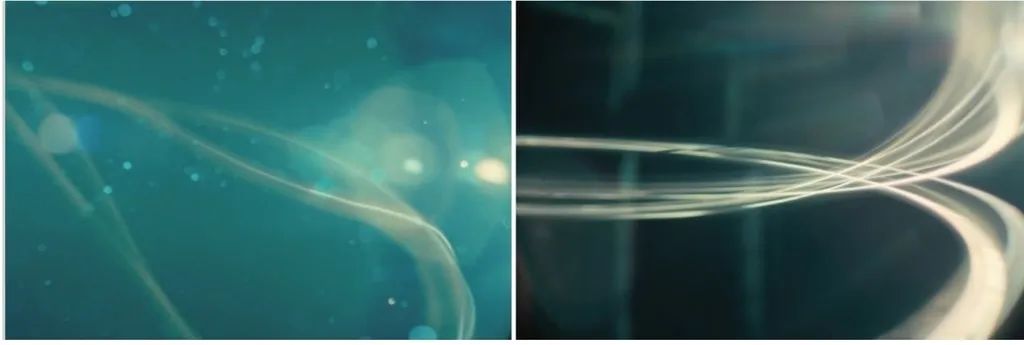

In “Oppenheimer”, a special application of the honeycomb COB light source is the almost underwater macro photography designed by Dneg’s Jackson and shot by visual effects photographer Dave Drzewiecki. Used to simulate microscopic visual effects.

These shots are designed to allow viewers to see what happens at the subatomic level with particles and energy waves. “It was impossible for an audience to actually observe this process, and Chris’s intention was to show how Oppenheimer imagined these physical processes,” Fisher explains. “We actually had a huge collection of photography,” Jackson noted. “Some of the photos were specific to a certain line in the script and could have been cut directly into the film, but others we weren’t sure what to do with, so they needed to be repositioned and resized. , flipped or layered on top of each other so that they become part of the plot development.”

Dolly mechanic Otis Mannick (left) and visual effects cinematographer Dave Javitsky shoot “subatomic” shots.

In the days leading up to the official filming of these scenes, Jackson extensively tested the actual rendering with digital cameras. “We didn’t start shooting on 15-perf 65mm film at 48 frames per second until we were absolutely sure what we were going to shoot,” he said. We customized the underwater housing for the honeycomb COB light source and used a 2×18-inch cylindrical water tank to create the lighting effect during the explosion, which contained wood chips, magnesium chips, aluminum flakes and aluminum powder, as well as thermite.

To photograph “Atomic Particles”, van Hoytema used a specially made macro lens designed and manufactured by Sasaki, which can be used with both 24mm and 35mm fixed-focus lenses. To put the chosen lens into action, they added a rubber-lined port on the side of the tank that allowed the axis of the lens to pass through the floating particles.

Dneg visual effects supervisor Andrew Jackson (left) and Javitsky measure a device.

For one of the atomic energy effects, Jackson simulated energy waves using wires connected to metal beads, which were rotated around an elastic central axis in a water tank by a motor. “When the central axis is bent, the arc of the rotating bead causes circles that were not touching to intersect,” Jackson said. The spinning wires were disturbed, creating ripples along their perimeter, which Jewecki photographed with long exposures, “so we had a long, wiggly, blurry line.” , represents the electron orbits around the nucleus,” Jackson said.

For frame rates above 48 frames per second, use an Arriflex 435 camera with a Panavision Primo fixed focus lens or Primo 11:1 zoom lens. “The white beads we used to photograph ‘atomic particles’ rotate around an elastic central axis, are painted matte black and are driven by a variable-speed motor,” explains Jievitsky. “The beads are at the end of a semi-rigid wire, like a welding rod. Likewise, the surface is painted matte black. The black line ends in a bead painted bright white.

From the shooting point of view, we just want to see the movement of the white bead. This is achieved through careful lighting and long exposures, depending on how fast the bead is spinning. Use a small matte black stick to create ‘disruption’. As the beads rotate around the track, Andrew Jackson will randomly ‘bump’ the black wire. When shooting with long exposures, the collision of the black lines will cause interesting swings or non-linear paths in the movement of the beads. Understanding and controlling the movement of the beads during this period is what really makes these shots come alive. “

During ten weeks of visual effects shooting, a total of more than 200 independent photographic elements were shot. “Throughout the entire shoot, Andrew and Scott collaborated with the main crew,” said Van Hoytema. “They were experimenting every day, and the results were good and bad, but they were always learning and summarizing what they had done before. lessons learned.”

innovative solutions

While filming No, Van Hoytema began running lights through a dimmer controller programmed by Chambers’ brother, Noah Shain. A year later, when filming “Oppenheimer,” nearly every light was battery-powered and equipped with wireless receivers and transmitters with virtually no lag, “so once the switch was flipped, we could control the lights to, “Our network is independent of regular Wi-Fi, which allows us to work quickly and efficiently over a large area,” said the cinematographer.

“Before this, our lighting process was very time-consuming,” Chambers said. “We would take out the lights, set them up, run the wires and connect them to the dimmer controller. The wireless CRMX signal would often fail, We couldn’t have any glitches.” “Hoyt was fed up with the limitations of existing technology,” Shane recalls. “He wanted to be able to control the lights above a building eight blocks away without running any wires, so I started Start doing it.” The first hurdle Shane faced was that the film industry lacked experience with TCP/IP networks, so he had to turn to industries that use wireless connections on a large scale, such as transportation.

If cruise ships, bus fleets and trains can all stay connected, then their systems can certainly meet our needs,” he reasoned. “Hoyt’s advice is key: ‘Be careful in tailoring your equipment. We need the system to be robust and flexible. If an innovation creates more problems than it solves, it won’t work. ‘” After months of independent research and experimentation, Shane developed two wireless systems based on Ubiquiti Air Max - an ultra-lightweight outdoor wireless base station used to establish long-range network connections in remote areas - to establish his own point-to-point A multipoint communication network, which he likens to “a bicycle wheel with a hub and spokes.” There are two types of “hubs” that transmit lighting data through the “spokes.” One is through a virtual machine running on an Amazon Web server. Private Networks (VPNs) use existing mobile cellular network infrastructure, giving operators total remote lighting control.

“As long as I’m within the coverage of the mobile cellular network, I can control the lights anytime, anywhere,” Shane said. In Oppenheimer, this system was used to shoot some of the driving scenes in New York and Los Angeles. Van Hoytema needed the lights to be mounted on the vehicle, complete with transmitters and batteries, allowing Shane to interact with the city. Ramin Shakibaei, the dimmer at the mobile lighting desk at the other end, keeps in touch.

Another “hub” system is a long-range wireless network generated by battery-powered Ethernet repeaters on a cart. “You can unload it from the truck, flip a switch, and it’s up and running in two minutes,” Chambers said. According to Shane, the Ubiquiti system’s wireless signal has virtually no lag within 15 miles of line-of-sight.

During the filming of “Oppenheimer,” the furthest they tested was three miles—a scene shot by aerial cinematographer Hans Bjerno at the Trinity nuclear test site, where the towers A series of runway-style “spherical” lights were lit around it, and the “gadget” (atomic bomb) was waiting to be ignited on the top of the tower. Shane was coordinating the lighting for this shot in the distant sand pit where the main camera crew was filming the scene immediately preceding this scene.

illuminate this moment

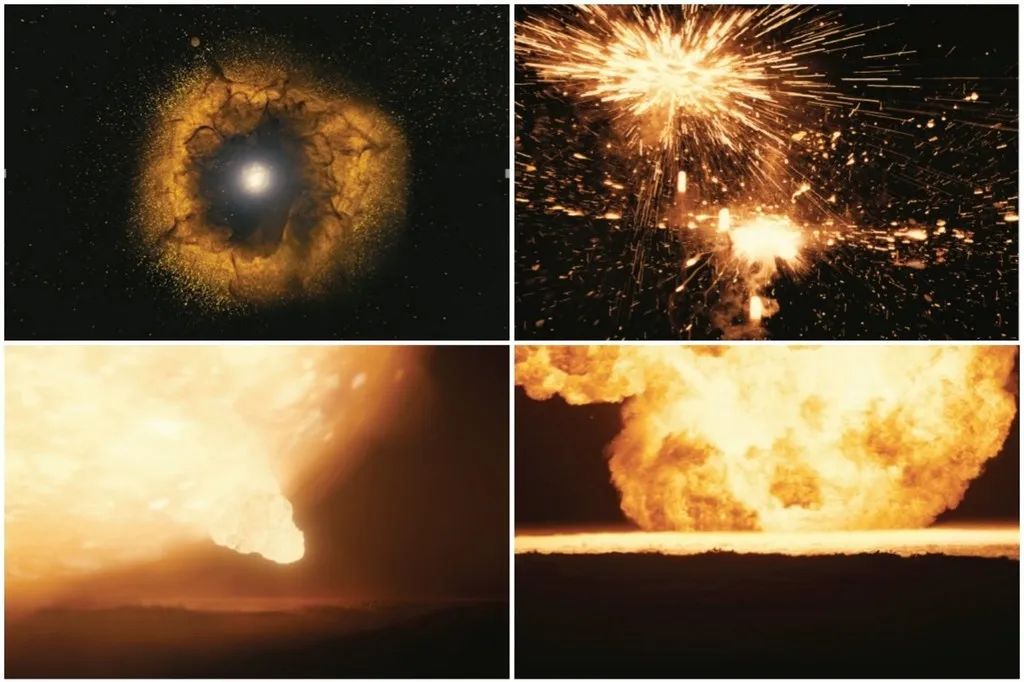

In order to simulate the effect of the dazzling light pouring out of the small window of Oppenheimer’s bunker during a nuclear explosion, the filmmakers finally decided to use ArriSkyPanel and Orbiter lamps.

“The task of simulating the effects of this explosion was monumental and pushed the simulation methods we used in filmmaking to the extreme,” Chambers said. The lighting engineer also added that although Nolan preferred tungsten lights and HMI lights compared to LED lights, the producers agreed that LED lights were best for shooting this scene. Van Hoytema saw the benefits of using LED lights, and both he and Nolan wanted the light from the explosion to cycle through the color spectrum—from red to blue.

Image

“Chris was really happy with this look,” says Chambers. “The Orbiter simulated the initial explosion, providing hard light at the beginning of the explosion, while the SkyPanel simulated the soft light coming through the clouds of the explosion. So, ( The combination of the two lights creates the overall visual effect of the entire explosion.” He added: “Another advantage of these lights is that we can quickly fine-tune them during rehearsal. Compared to strictly using tungsten lights, or HMI lights, which gives Hoyt more time on lighting.”

Channels of Progress

The key to the wireless networking technology used in “Oppenheimer” is that it is open source, meaning anyone who understands the system’s architecture can assemble it themselves and customize it to specific needs. Shane sees his innovation as useful, “so I wouldn’t really keep it a secret,” he said. “In a sense, our job as cinematographers is to convey a message,” Van Hoytema points out.

Chambers agrees: “Hoyt and Chris really care about film as an art form, and they want the art to flourish. Sharing technology gives everyone the opportunity to advance faster.” Technology Once mastered and formed for the sake of art, it now often feels like guiding the art we create,” says van Hoytema. “We shouldn’t just limit ourselves to existing technologies. Next time Rent equipment, talk to an engineer and have them customize something for you, like a special lens for a special effect. Or do it yourself. The technology should be in your hands.”

Readers who are interested in the original text of this article are welcome to search for the latest electronic version of the 2023-October issue on the official website of the Film and Television Industry Network and the “Heroes Behind the Scenes APP” for detailed information. Download the Behind-the-Scenes Heroes APP of the Film and Television Industry Network and read the complete Chinese version of “American Cinematographer Magazine” for free. Learn more about filming in the United States.